In this part of the series, I'll demonstrate generating HTTP responses from a simple Node.js Express server. You can view all of the code in the Github repository. After this, in A Beginner's Guide to HTTP - Part 3: Requests, we'll generate request messages to get the responses we build here.

Building an HTTP message conversation is like communicating via telegraph or secret code. When the server receives a request message, it has to decode it to get the instructions for the response message. Based on those instructions, the server encodes and returns a response message.

Introduction and Table of Contents

This article assumes familiarity with basic JavaScript, command line, and the terms defined in part 1.

I'm starting with the server/HTTP responses because you'll usually find yourself building HTTP request code around the HTTP response format you're receiving. (You'll see this pattern repeatedly in part 4, when we use APIs other people have built.)

- A Simple Node.js Express Server

- URLs, Routes, and Endpoints

- URL Parameters

- Status Codes and Error Handling

- My Fake Yarn Database

- DELETE and Postman

- Body Parsing and Middleware

- POST and JSON

- CORS

A Simple Node.js Express Server

I'll be making a very simple yarn stash app, so I can keep track of all of my yarn. As you follow along, try building your own app idea, whatever it may be. You'll be surprised how much tweaking the code slightly helps you learn the concepts, and you may even go on to finish a cool app from the CRUD bones you create here. I've still got one or two apps from bootcamp that started like this that I enjoy working on.

To follow this tutorial, you'll need to install Node.js. (If at first you don't succeed, take a break and try again. There's a reason professional developers complain about setting up their development environments.)

Start by creating a main project folder. If you haven't thought of an app name yet, you can use a placeholder name or app name generator. Inside it, create a folder called server.

npm is the package manager installed with Node.js to manage and install packages/libraries of code. It is also the name of the registry from which the package manager gets said packages. The registry is free to use and you can upload your own packages. Commands you run using npm, the package manager, will start with npm.

Navigate to your server folder in a terminal, and run npm install express. We could set up a server with just Node.js, but Express is a beginner-friendly web framework library we can run in Node.js. That command will have generated some folders and files.

Within your server folder, add a file called app.js. Open app.js in a text editor, and add this code:

const express = require('express')

const app = express()

const port = 8080

app.listen(port, () => {

console.log("Server is running on port 8080...")

})

This code instantiates or makes an instance of an Express server I've called app. Now any HTTP messages sent to http:localhost:8080 will be handled by app.

Next run node app.js in your terminal to run the server. If it works, you should see "Server is running on port 8080..." logged in your terminal. Use crtl + C to kill the server. Every time you change the server code, you'll either have to kill the server and run it again or use a tool like nodemon that watches for newly saved changes in your files and restarts the server for you.

Now that our server is running, let's talk about setting up our routes.

URLs, Routes, and Endpoints

URL stands for Uniform Resource Locator, a specific type of Uniform Resource Identifier (URI). Basically, a street address but for a client or server hosted on the web. In part 1, we talked about how a URL has a protocol (http:// or https://). I mentioned that ports were optional. If you're accessing a URL that uses HTTP or HTTPS, the port is not specified as long as the standard port is used (80 for HTTP and 443 for HTTPS). My server is running on port 8080 on my local machine, so its URL is localhost:8080. After the protocol, domain/host name (localhost for my server), and maybe a port number, you can pack a lot of information into a URL.

You may be familiar with the terms route, routing, and router. Much like your wifi router helps your devices access different routes on the internet, a server has a router that specifies what happens when someone types that URL into the browser. If you've already been building webpages, you've made routes. In localhost:3000/index.html, index.html could be called a route. As you build bigger and more complex front-ends, you may end up building and installing routers in your client too.

Let's set up our most basic route:

app.get('/', (req, res) => {

res.send('Welcome to the yarn server!')

})

This tells the server that if an HTTP GET request message is sent to our main route (req stands for request), it should execute the arrow function. The arrow function sends back an HTTP response message (res stands for response) with the string 'Welcome to the yarn server!' in the body. The arrow function is called a route handler.

Run your server again, and this time, navigate to http://localhost:8080 in your browser. You should see 'Welcome to the yarn server!' displayed on the page. By typing that URL into the browser, you sent an HTTP GET request to your server to the route /. http://localhost:8080 is the same as http://localhost:8080/. The server then decoded your GET request and sent back a response. The browser decoded the response and displayed it for you.

Next, we'll create a route that will send back all of the yarn data, /yarn. It will look like this:

app.get('/yarn', (req, res) => {

res.send('This is all of the yarn data!')

})

With this, if you navigate to http://localhost:8080/yarn with your server running, you'll see 'This is all of the yarn data!'.

Since my server is tiny, there are a lot of routing methods provided by Express that I won't be using. A method in this context is a function associated with an object. In the previous code, app.get() is a method. array.find() is a built-in JavaScript method. You also don't have to use arrow functions - you could pass a named function to app.get().

If I were building a complex app, say one that was concerned with yarn and knitting patterns, I could set up router files outside of my main server file. Then I could have a /yarn router that would handle any routes starting with /yarn (like /yarn/purple and /yarn/green) and a /pattern router that would handle any pattern routes (like /pattern/hats and /pattern/scarves).

From the perspective of a client wanting to request a resource from a server, /yarn in http://localhost:8080/yarn would be called an endpoint. For example, in the DEV API documentation, you can see how /articles is called the "articles endpoint" and the entire URL is https://dev.to/api/articles. If you make a GET HTTP request to https://dev.to/api/articles, DEV's server will return all the posts users create on DEV. So developers will say in conversation, "making a GET request to the articles endpoint will return all the posts users create on DEV." Meanwhile, the developer building the DEV API would probably say something like "the articles route will send back all the posts users create on DEV."

URL Parameters

If I want to make it easy to request data about one yarn instead of all the data about all the yarn, I can require the HTTP request pass an id in a URL parameter. The server route code would look like this:

app.get('/yarn/:id', (req, res) => {

res.send(`This is the yarn data for ${req.params.id}.`)

})

Just like we used the res object passed to our route function to send a response, we use the req object to reference the request message sent to this route. With this code, we get the id from the HTTP request message's URL, and send it back in a string.

With your server running, navigate to http://localhost:8080/yarn/23 in your browser, and you should see "This is the yarn data for 23."

Status Codes and Error Handling

If you don't specify a status code when you send your response, Express uses Node.js code to send 200. If you wanted to explicitly send a status code (and the associated message), you can chain it and the .send() function like this:

app.get('/yarn/:id', (req, res) => {

res.status(200).send(`This is the yarn data for ${req.params.id}.`)

})

Express has built in error handling. If an error is not handled by code you've written, Express will send a response with the status code 500 and the associated status message. If you wanted to specify which error status code to send within your route handler, it would look very similar:

app.get('/yarn/:id', (req, res) => {

if (isNaN(req.params.id)) {

res.status(404).send("No id no yarn!")

} else {

res.status(200).send(`This is the yarn data for ${req.params.id}.`)

}

})

This way, if I navigate to http:localhost:8080/yarn/purple in my browser with my server running, I'll see "No id no yarn!" If I navigate to http:localhost:8080/yarn/43, I'll see "This is the yarn data for 43." The browser does not display the status code or status message for us, but I'll soon introduce a tool that will.

My Fake Yarn Database

I'm going to mock a database really quickly by using an array of objects in my server to hold data. This means any data that is not hardcoded will disappear every time I kill my server, but setting up a database is beyond the goal of this guide.

Along with yarn name, I want to record yarn weight, color, and how many meters I have, so I add this array to the top of my file:

let yarnDB = [

{

id: 1,

name: "I Feel Like Dyeing Sock 75/25",

weight: "Fingering",

meters: 299.7

},

{

id: 2,

name: "Magpie Fibers Swanky Sock",

weight: "Fingering",

meters: 1097.3

},

{

id: 3,

name: "Rowan Alpaca Colour",

weight: "DK",

meters: 18

},

{

id: 4,

name: "Malabrigo Yarn Rios",

weight: "Worsted",

meters: 192

}

]

First, I'll change my route that returns information about all the yarn in my "database."

app.get('/yarn', (req, res) => {

let yarns = yarnDB.map(yarn => `Yarn ${yarn.id} is named ${yarn.name}. It is ${yarn.weight} weight and you have ${yarn.meters} meters.`)

res.send(yarns)

})

Then I'll also change my /yarn/:id route handler to return information about specific yarns in the array:

app.get('/yarn/:id', (req, res) => {

let yarn

for (let i=0; i < yarnDB.length; i++) {

if (yarnDB[i].id === parseInt(req.params.id)) {

yarn = yarnDB[i]

}

}

if (yarn) {

res.send(`Yarn ${req.params.id} is named ${yarn.name}. It is ${yarn.weight} weight and you have ${yarn.meters} meters.`)

} else {

res.status(404).send("No yarn with that id.")

}

})

Navigating to http://localhost:8080/yarn/3 in my browser with my server running returns "Yarn 3 is named Rowan Alpaca Colour. It is DK weight and you have 18 meters." Navigating to http://localhost:8080/yarn/5 returns "No yarn with that id." Navigating to http://localhost:8080/yarn will turn an array of yarn information strings for every yarn in the "database."

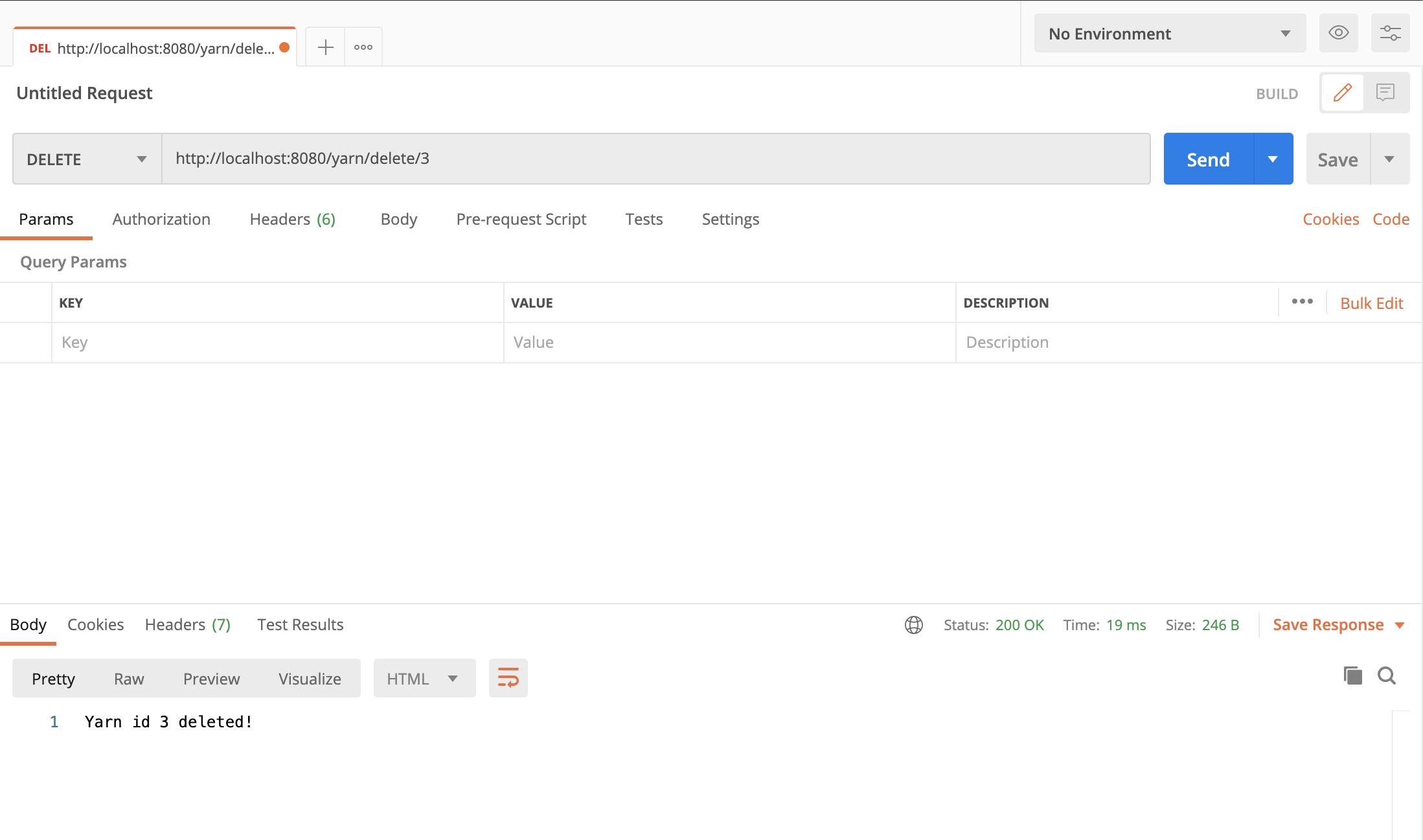

DELETE and Postman

You may have noticed - I've only made routes with the GET method so far! We have no way to add or delete yarn! That's because we can only generate GET requests using a URL in the browser. To use a POST or DELETE route, you'll need a client or a tool like Postman. We'll build our client next, but first, let's cover how to use Postman to test my DELETE route:

app.delete('/yarn/delete/:id', (req, res) => {

let index

for (let i=0; i < yarnDB.length; i++) {

if (yarnDB[i].id === parseInt(req.params.id)) {

index = i

}

}

if (index === 0 || index) {

yarnDB.splice(index, 1)

console.log(yarnDB)

res.send(`Yarn id ${req.params.id} deleted!`)

} else {

res.status(404).send("No yarn with that id.")

}

})

Once you have Postman installed and open, you'll need to open a new request tab and enter the information required to build a request. For the DELETE route, all you have to do is select the DELETE method from the drop down and type in the URL. If I enter http://localhost:8080/yarn/delete/3, and hit the send button, I see "Yarn id 3 deleted!" in the response body in Postman. When the array is logged in the server terminal, I only see yarns 1, 2, and 4 in my yarnDB array now.

The response section in Postman also shows us some information about the HTTP response message that we couldn't see in the browser. The status code and message are shown right by the response body. Both the request and response sections have tabs like headers where you can see all the headers for the message and other information and tools. Check out Postman's docs to see all the tools it can provide.

Body Parsing and Middleware

I also need to add a body parser to decode my request body data into something I can work with in JavaScript in my server. This is why both requests and responses use Content-Type headers. Translating an HTTP message body into something useful is significantly easier if we know what the body's media/MIME type is.

I add some middleware in my server file so that my Express server will automatically parse JSON in the body of requests it receives:

app.use(express.json())

In this context, middleware refers to functions outside of the route handler executed when an HTTP message triggers a route in the server. By using app.use() I'm telling app to run the built in JSON body parser Express provides before every route handler that receives a request body is executed.

Express also provides methods for writing your own middleware, including error handling middleware. You can run middleware on every route or call middleware before or after specific routes execute. For example, if a route added data to your database, you might want to run logging middleware before the route handler is executed to say that adding data was attempted and after the route handler is executed to log whether it was successful.

If you want to know more about middleware, including error handlers, and more about what you can do with Express, check out the LogRocket guide.

"But wait," you might be thinking, "we've been sending data without specifying the Content Type header or formatting the body this whole time!" Express's res.send() method automatically sets headers and formats the body based on the type of the parameter passed to it,-Sends%20the%20HTTP). Using res.json() instead of res.send() would set the Content Type header to "application/json" and format whatever is passed as JSON. You can also use res.type() to set the header yourself. This is the main reason I chose Express for this guide - the formatting and parsing of HTTP messages will only get more manual as we go on.

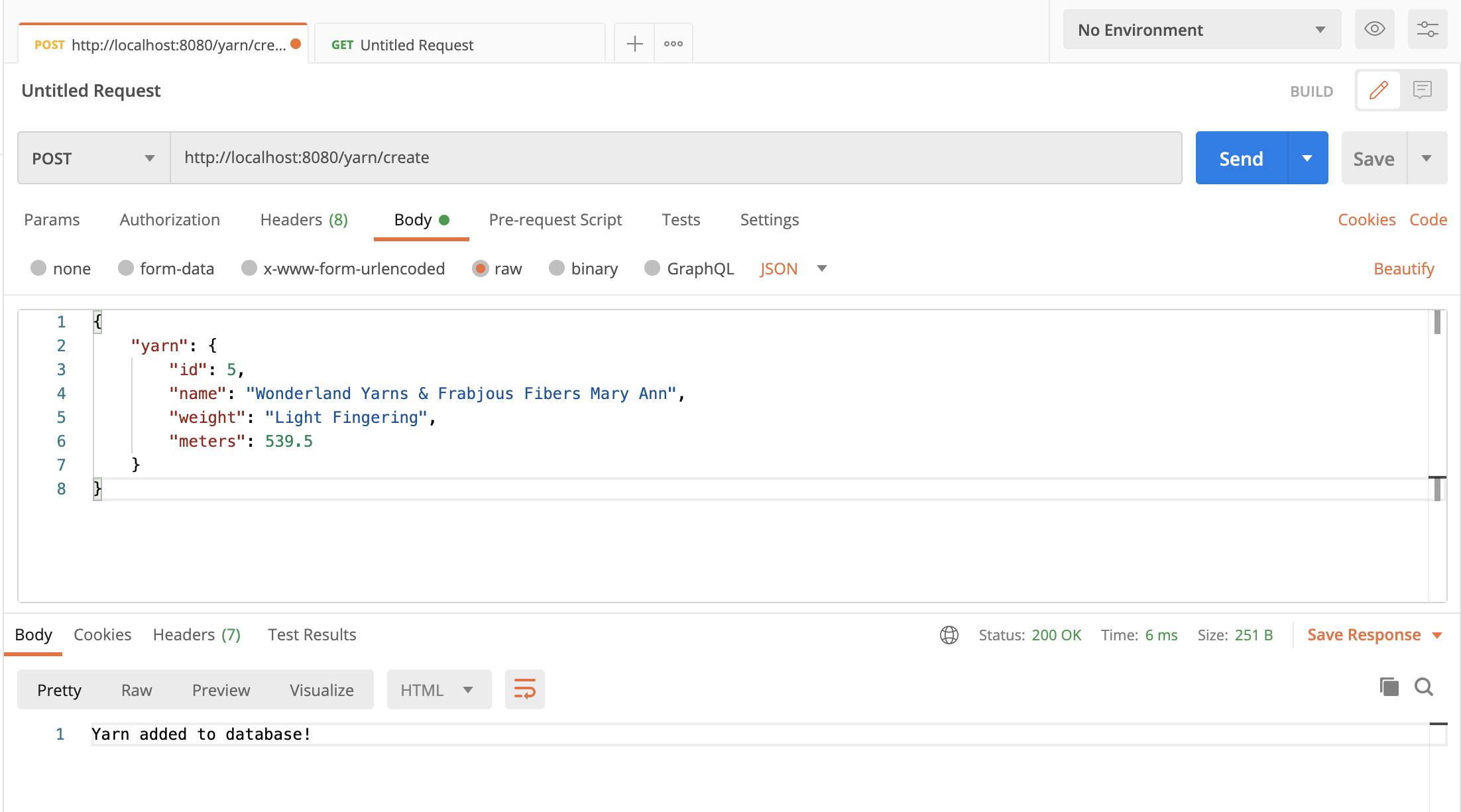

POST and JSON

Next up, my POST route:

app.post('/yarn/create', (req, res) => {

let yarn = req.body.yarn

if (yarn.id && yarn.name && yarn.weight && yarn.meters) {

yarnDB.push(yarn)

console.log(yarnDB)

res.send("Yarn added to database!")

} else {

res.status(400).statusMessage("Yarn object not formatted correctly.")

}

})

(In the real world, I would validate data sent to my server a lot more before adding it to my database. This code allows me to add the same yarn object multiple times. It doesn't check the body's structure and I'm not checking if the fields are the correct data type.)

To test this route, I'll need to build a valid JSON string to pass in the body of my HTTP request. In practice, writing JSON boils down to building a JavaScript object or array, but nothing can be a variable. For example, this is a valid JavaScript object:

let person = {

name: "George"

}

In JavaScript, I could access person.name and get "George". To be valid JSON, object and field names have to be strings and everything must be contained in an object or an array:

{ "person":

{

"name": "George"

}

}

Once my server uses the express.json() middleware, that JSON string will be turned back into a JavaScript object and we can access person.name to get "George" again.

To be able to access req.body.yarn in my route handler, my JSON will look like this:

{

"yarn": {

"id": 5,

"name": "Wonderland Yarns & Frabjous Fibers Mary Ann",

"weight": "Light Fingering",

"meters": 539.5

}

}

"Hold on a second!" you might be saying, "5 and 539.5 aren't strings!" That's because JSON allows multiple data types to be used. To get used to translating data into valid JSON, try using a JSON parser like JSON formatter. They even have an example with all the possible data types you can play with. We'll cover the methods available within JavaScript to convert objects between JSON and JavaScript soon, but being able to recognize valid JSON will help when you're trying to troubleshoot down the road.

To use the POST route with Postman, we'll have to create a body. After selecting POST from the drop down and entering http://localhost:8080/yarn/create, I move down to the request tabs and select the body tab. Next I select the radio button labelled raw. Then, from the dropdown that appears next to the radio buttons, I select JSON and enter my JSON object into the box below. When I hit the send button, I see "Yarn added to database!" in Postman and the array logged in my server confirms yarn #5 has been added to my array.

CORS

Postman ignores CORS. Even though we've got our basic server set up to send HTTP responses once it's received HTTP requests, we still need to enable CORS before we move on to generating HTTP requests in a client. To do this, I install the cors package by running npm install cors in my terminal. At the top of my app.js file, I import the package:

const cors = require('cors')

Then, I add the CORS middleware on every route, just like the body parser:

app.use(cors())

This is the equivalent of adding this header to every pre-flight and response message sent by this server:

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *

* is a wildcard. This tells browsers to allow any request from any origin. This is the least amount of security possible. Since my goal is to practice HTTP requests on my local machine, I'm going with the easiest option. If this was a server I was going to deploy, I would use the configuration options to limit origins and methods that can access my server.

Conclusion

If you're left confused or have any questions about any of the topics I've touched on in this part of the series, please don't hesitate to leave a comment! I made an effort to link to resources for topics when they came up, but if there are topics you'd like to see in a "more resources" section like in part 1, let me know.

I wanted to start with the server not only because you'll usually build request messages and write client code based on the format of the response messages you want to use, but also it's much easier to wrap your head around what's happening when you know what to expect in a response from the server. Now we're ready to build a client to request these responses in A Beginner's Guide to HTTP - Part 3: Requests!