As a web developer, I sometimes describe my job as "making things talk to each other over the internet." HTTP, which stands for Hypertext Transfer Protocol, makes this possible. In other words, HTTP is a method of sending messages from one program to another using the internet.

In this article, I'll cover HTTP terms, tools, and the structure of HTTP messages. I use analogies and metaphors, and explain things in multiple ways to try and provide helpful mental models. In A Beginner's Guide to HTTP - Part 2: Responses, I'll dig into how to write the code to generate HTTP response messages in a server. After that, in A Beginner's Guide to HTTP - Part 3: Requests, I'll cover how to generate HTTP requests in a client. We'll have a little fun with our app and some free to use APIs that other people have built for us in A Beginner's Guide to HTTP - Part 4: APIs. Finally, I'll cover API keys and more in A Beginner's Guide to HTTP - Part 5: Authentication.

Introduction and Table of Contents

This article assumes familiarity with basic JavaScript. I briefly explain asynchronous JavaScript and basic web development concepts and provide more learning resources at the end of the article.

I will not be explaining TCP, the many definitions of the word "protocol," or how the internet works. This is a general overview and guide to using HTTP messages in your web application.

- Web Development Terms

- HTTP Terms, Asynchronous JavaScript, and HTTP Tools

- Structure of a Request

- Methods

- Request Headers

- Request Body

- Structure of a Response

- Status Codes and Messages

- CORS

- More Resources

Web Development Terms

First, let's define a few terms I will be using a lot. An application or application program is software that runs on a computer. The basic set up of most web applications is a client application that runs in a browser like Chrome, Firefox, or Safari and a server application that provides services and resources for the client. In this way, the browser is functioning as a runtime environment for client or client-side code. In JavaScript, the most common runtime environment used for server or server-side code is Node.js. Put another way, the client is the part of the code that the user interacts with - clicking buttons or reading information on a page in their browser. To get the information the user wants to read or to get or update information after a user clicks something, my client will talk to my server using HTTP.

I often use "app" to refer to my client, because not every web application needs a server. It is possible to have a web app with only a client, like a calculator that can perform all of its math without getting any more information from another resource. It is possible to only build a client and use server-side resources built by other people. You may have seen the term "serverless," which refers to ways to create server-like services and resources without building a server yourself. In reality, serverless apps involve building a client and then using tools like AWS or Netlify to write server-side code inside the client. When needed, your client will then use the tool to execute the server-side code on a server built and hosted by other people. For the purpose of learning HTTP in this guide, we will be focusing on the classic client-server model I described above.

I won't be using "front-end" and "back-end," because "client" and "server" are more specific. For example, the back-end of a web app would include not only a server but also a database and any other services and tools used by the server.

API stands for Application Programming Interface. It allows two applications, like a client and a server, to talk to each other. If the server is the whole restaurant, the API is the waiter, the menu is the list of methods the API provides, and the hungry customer is the client. I'll cover standardized formats for APIs and more in part 4.

A library is a package/collection/module of files and functions that a developer can use in the program they're writing. Because API is a broad term and APIs aren't only used for the client-server model, the methods provided by a library for the developer to use can also be referred to as an API.

HTTP Terms, Asynchronous JavaScript, and HTTP Tools

There are different versions of HTTP. HTTP/2 is more optimized and secure than HTTP/1.1, and about half of websites use it. There's even an HTTP/3, developed by Google. You may already be familiar with seeing http:// and https:// in your URLs and browser warnings about security. HTTP messages are encrypted when sent using HTTPS, and are not encrypted when sent using HTTP.

There are several libraries you can use to send HTTP messages. For example, curl can be used from the command line. They all use HTTP, so the information they need is the same. What differs is where you can use them, the syntax to create HTTP messages, the options they provide, and the protocol they use (e.g. HTTP vs HTTPS, HTTP/1.1 vs HTTP/2). More robust libraries will do extra things.

When looking at JavaScript HTTP libraries, you may come across the term AJAX or Ajax. It stands for Asynchronous JavaScript and XML. Put very simply, asynchronous code runs out of order. Sending a message over the internet and getting a message back takes time. Asynchronous code can essentially pause execution until the data is received and then pick up where it left off. XML stands for Extensible Markup Language. It's like HTML, but without predefined tags. It is one format used to structure data you might send within an HTTP message. Ajax can refer to using HTTP with JavaScript even if the message doesn't contain data or the data is not structured with XML.

When you write JavaScript and it is running in a browser, you have access to a lot of built in tools. It's hard to imagine building a website without Web APIs like the HTML DOM and URLs. For a long time, the only HTTP Web API available was XMLHttpRequest or XHR. Because it was an Ajax library, it finally allowed web pages to pull data from a database without having to refresh the whole page.

The more modern version, supported by all browsers except IE, is Fetch. Support for Fetch was just included in the latest version of Node.js in January 2022. It builds on XHR by providing interfaces (expected formats) for both halves of the HTTP conversation and where XHR uses Callbacks, Fetch uses Promises.

Callbacks and Promises are pretty big topics. Essentially, a Callback function is passed as an argument to an asynchronous (async) function. After the async function gets what it needs, then the Callback function is executed. Promises, on the other hand, are objects returned by async functions. They have three states, pending, fulfilled, and rejected. Async functions that return Promises can be chained with .then() and .catch(). This way, the developer can pass the returned fulfilled Promise to a function in .then() or pass the returned rejected Promise to .catch() and handle the error. Javascript also has async/await syntax that uses Promises without having to explicitly create Promise objects or pass them to a chain. (You can still chain them if you want, though.) Other functions can call await asyncFunction() and wait for the result before continuing execution. Often, the result of the function call is set to a variable to be used later. I'll have code examples in part 3 and more resources for learning about these topics at the end of this article.

Finally, there are packages like Axios. Not only does Axios provide interfaces and use Promises, but it also allows the developer to make both client-side HTTP requests in the browser using XHR and server-side HTTP requests in Node.js. It also provides more options and formats your messages for you.

Before we get into how to write the code that sends the HTTP messages across the internet in part 2 and part 3, let's dive into how the messages themselves are structured.

Structure of a Request

If we say a client and a server are having a conversation, the two halves of the conversation are a request and a response. Using an HTTP request, a client is requesting something from a server.

Every request requires some information to work:

- Method: The method tells the server what the client wants it to do.

- URL: The URL tells the HTTP tool where to send the request.

- Protocol: Set by the HTTP tool used.

- Headers: Headers give the server more information about the request itself.

The URL in the HTTP request message works just like when you type in a URL to go to a webpage in your browser. The URL can also be used to send additional information - I'll explain more about URLs and how to use them in part 2.

There is also an optional part:

- Body: If a request uses a method that sends data to the server, the data is included in the body, right after the headers.

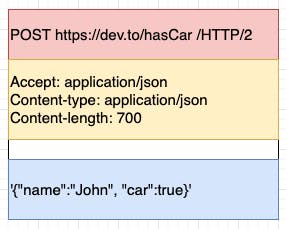

So an HTTP request message would look something like this:

The first line, shown here in red, has the method, URL, and protocol. The second, yellow portion has all the headers. There's a blank line and then if there's a body, it goes at the end, shown here in blue.

Methods

The easiest way to explain methods is to map them to the persistent storage acronym, CRUD. CRUD stands for Create, Read, Update, and Delete. You can think about it in terms of database that uses SQL:

Create = INSERT Read = SELECT Update = UPDATE Delete = DELETE

You can think about it in terms of an app's UI:

Create = users making a new post Read = users looking at their newsfeed Update = users editing a post Delete = users deleting a post

For HTTP requests:

Create = POST Read = GET Update = PUT or PATCH Delete = DELETE

Note: There are more methods I didn't cover, because I have yet to use them.

POST sends data to the server and results in a change. It requires a body. GET requests data from the server be sent back via response. It does not have a body. PUT sends data to the server to create a new resource or replace an existing resource. It requires a body. PATCH sends data to the server to update part of an existing resource. It requires a body. DELETE requests a resource be deleted. It may have a body if the information required to identify the resource to be deleted is not contained in the URL.

Request Headers

There are a lot of HTTP request headers. If the server is a concert, and the HTTP request is an attendee, the headers are like the attendee's ticket and ID. An Origin header would tell the server where the request came from. An Accept header would tell the server what kind of format the server should use for its response. A Content-Type header tells the server what kind of format the request body is using. Some of them are automatically made by the HTTP library. Some, like Authentication headers, are dictated by the server. I'll cover Authentication in part 4, when I request data from an API that requires a key. Many headers you'll find on both the request and the response. If the HTTP specification refers to a header as a request header, it only gives information about the context of a request. Developers will refer to headers included in a request as request headers in conversation, even if they could also be used as a response header and vice versa.

Request Body

HTTP message bodies can be packaged in several standardized data transfer formats. The formats are referred to as media types or MIME types, and there are many of them. XML and JSON are the two you are going to see most often. They both create single-resource bodies, which means they are one file in the HTTP message body.

JSON stands for JavaScript Object Notation. It has a standard syntax that creates smaller files. JavaScript built-in methods easily turn the JSON string into valid JavaScript objects. JSON can only be encoded in UTF-8 and has types. XML is typeless, can keep the original data's structure, supports multiple types of encoding, is more secure, and can be displayed in a browser without any changes. XML requires work to parse into JavaScript and is more difficult for humans to read but easier for machines to read. XML vs JSON, how JSON came to be the most widely used HTTP data transfer format, and what other formats still exist is a huge topic. Twobithistory's synopsis will start you down the rabbit hole. I'll be using JSON and covering its syntax and the built-in JavaScript methods in part 2 and part 3.

The MIME type and character encoding used in a request body are declared in the Content-Type request header so the server knows how to decode and handle the data in the body of the request. XML content would have application/xml in the header. JSON content would have application/json.

The best example of a multiple-resource body is data sent from an HTML form on a webpage. It would have multipart/form-data in the Content-Type header. Instead of one body, there are multiple bodies, one for each part of the form, each with its own Content-Type header. Thus, data the user entered can be sent to the server along with the properties of the HTML element they used to enter it. As a result, if you have an <input> with a property like name="first_name", the request body will include "name='first_name'" with the name the user typed into the <input>.

Structure of a Response

After a client sends an HTTP request, the server sends back an HTTP response. Every response sends back some information:

- Protocol: Set by the HTTP tool being used.

- Status Code: A set of numbers that will tell you how the process from request to response went.

- Status Message: A human readable description that will tell you how the process from request to response went.

- Headers: Gives the client more information about the response itself.

There is also an optional part:

- Body: If the response contains data from the server, it will be included here. Request and response bodies use the same formats.

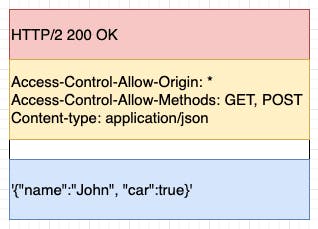

So an HTTP response message would look something like this:

The first line, shown here in red, has the protocol, status code and status message. Next, the yellow section has the headers. The headers are followed by a single blank line. Finally, if there is data to send back, there is a body, shown here in blue.

Status Codes and Messages

You've encountered status codes before while using the internet. Everyone's seen "404 Not Found" and you may have seen "403 Forbidden." The one you'll be hoping for when writing HTTP requests is a successful "200 OK." The ones you don't want to see when writing client-side code are in the 400s like "400 Bad Request" and "405 Method Not Allowed." Problems with the server will be in the 500s like "500 Internal Service Error" or "503 Service Unavailable."

Technically, these are standardized. The problem is, people are writing what response to send back and they can choose whatever status code and message they want. Ideally, responses from a resource you didn't build will use the standardized codes and messages. You'll often find you have to read the documentation or interact with the resource to find out how to handle their response format.

If you'd prefer to learn your status codes and messages accompanied by animal pictures, check out HTTP Cats and HTTP Status Dogs.

CORS

Since the majority, but not all, of the CORS headers are request headers, let's dive into CORS here.

CORS stands for Cross-Origin Resource Sharing. By default, browsers and servers running JavaScript use CORS to block requests from a client with a different origin than the server for security. The goal of CORS is to protect the client and server from executing malicious code contained in an HTTP request and to prevent data being stolen from the server.

For most browsers, origin refers to the host, the protocol, and the port, if the port is specified. The host is the part of the URL after www. and before a /. So for google.com, the host is google.com. The protocol is HTTP vs HTTPS and HTTP/1.1 vs HTTP/2. The port would be 3000 in localhost:3000.

Before your original request is sent, HTTP will send a preflight request with some headers like the origin and the method to check if the request you want to make is safe. The server then sends back a preflight response with CORS headers like Access-Control-Allow-Origin and Access-Control-Allow-Methods that tell the browser whether the original request is allowed. This is when a request will be blocked by CORS if it's going to be.

You can only dictate if a server allows CORS requests if you are writing the server code. For example, a server's response will include the Access-Control-Allow-Origin header to list the origins that can receive the request. If your origin isn't in the list in the Access-Control-Allow-Origin header in the response, your request will be blocked, and you can't change that unless you are writing the code that sends the responses.

If a server relaxes CORS restrictions, they will typically replace it with required authentication or use the Access-Control-Allow-Methods header to restrict request methods to GET only. Authentication can be sent in the headers or the URL (more on that in part 4).

However, even if the server allows CORS requests, your browser will block a CORS request in your client-side code. You can get around this by requesting data from the server using your own server and then passing what you needed from the response to your client.

More Resources

If you're just dipping your toe into asynchronous Javascript, I highly recommend dropping everything and watching two videos right now: Philip Roberts' "What the heck is the event loop anyway?" and Jake Archibald's "In The Loop".

Callbacks and Promises are difficult concepts and I explained them very quickly. I only truly understood them after writing code with them every day for months. It is in your best interests to learn about Callbacks before moving on to Promises, as Promise objects and chaining provide their own challenges. Here are a few more resources that should help you wrap your mind around them:

- digitalocean.com/community/tutorials/unders..

- better.dev/callbacks-promises-and-async

- theunlikelydeveloper.com/javascript-callbacks

- bitsofco.de/javascript-promises-101

- ebooks.humanwhocodes.com/promises

- javascript.info/async-await

Conclusion

That was a lot of definitions before we get to any code! HTTP messages are complex, but they're also the bread and butter of web applications. If you are left confused or wanting more resources about a topic I touched on, don't hesitate to leave a comment below.

Next, check out A Beginner's Guide to HTTP - Part 2: Responses!