The last blog covered adding your changes to a remote branch, but what if other developers are working in the repo at the same time as you? How do you add changes from one branch to another?

Merging

The default for adding changes in one branch to another is merging. The other option is rebasing.

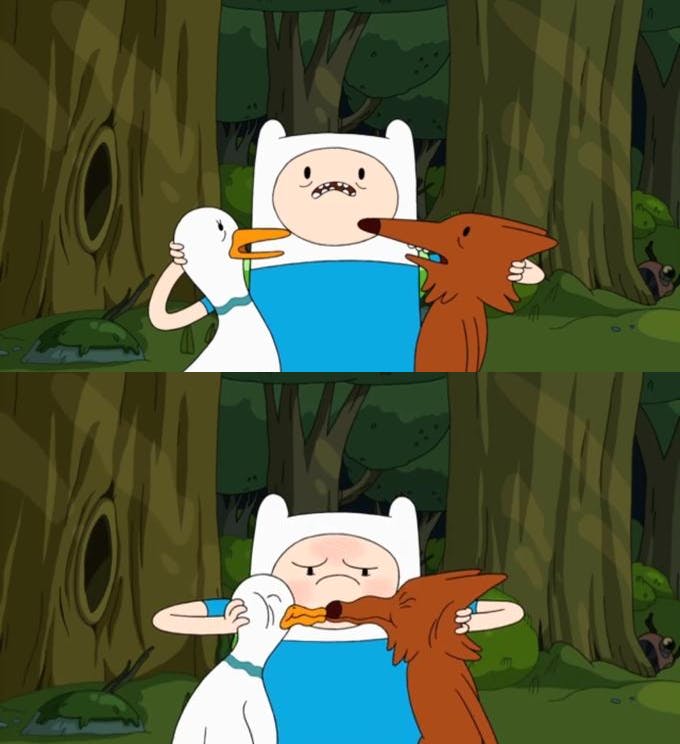

Rebasing looks at all the commits and has them line up single-file in an order that makes sense. Merge takes all the changes and smushes the two branches together like it's saying "now kiss," takes notes on how they kiss, and then slaps those notes on the end of the commit history.

To make it more complicated, technically there are two kinds of merging. When you run

git merge new-branch

git will try to merge the branch named new-branch into the branch you currently have checked out. It starts with the the easiest option, a fast-forward merge.

Fast-Forward Merge

To start, a merge finds the last common commit in both branches. Let's say you were in the main branch and created a new branch based off of it by running git checkout -b new-branch. The last commit in main before you ran that command is the last common commit.

By the time you're ready to merge, no new commits have been added to the main branch. In other words, all the new commits in new-branch come right after the last common commit. All git has to do is add the new commits from new-branch right after the last common commit in main.

This is a fast-forward merge. It uses rebasing under the hood, so it doesn't create a merge commit. Pushing will only fast-forward merge.

3-way Merge

If a fast-forward merge is not possible, git will try a 3-way merge. (Unless you're pushing, then you'll just get an error.)

Let's say you've been working on a feature in new-branch for a couple weeks. In that time, your co-worker completed a feature and it's been merged into main. A 3-way merge takes into account new commits in main that don't exist in new-branch.

The name comes from the three commits git is comparing - the last common commit, the last commit on main, and the last commit on new-branch. It looks at how the changes in main and new-branch diverge from the last common commit. Based on those snapshots, git creates a new merge commit with all the changes on the end of the commit history.

Squash Merge

You can squash both a fast-forward merge and a 3-way merge by running

git merge --squash

This option takes all of the individual commits, puts all the changes in one commit, and allows you to write one, comprehensive message. This improves commit message history readability by decluttering.

Rebasing

To run a standard rebase, use

git rebase new-branch

and git will rebase all the commits in new-branch on top of the last commit in the branch you have checked out. In other words, it updates the commit history in the branch you have checked out with the new commits from new-branch.

Because this is not a fast-forward merge, you will have to force push to rewrite the commit history in the remote branch. Default to running

git push --force-with-lease

so that that it will not overwrite any work on the remote branch that you don't have in your local branch.

This understanding of merge vs rebase is already a powerful tool in your tool belt. If you want full control over your commit history, you can use interactive rebase. It's a powerful tool and complicated enough that I've chosen to cover it separately.

Cherry-picking

The other option you have is to checkout the branch you want to add the changes to and manually move each commit. To do this, you would run

git cherry-pick <SHA>

where SHA is the unique identifier for the commit. You can find the SHA in the commit in the GitHub UI or by using git log. However, this creates a new SHA for the commit on the new branch. If you go to merge two branches with the same changes, but one commit was cherry-picked, git will not consider them the same commit.

Conflicts

When you combine branches, git often runs into situations where it doesn't know how to apply the changes. Each time it doesn't know what to do with your new code is called a conflict. It will show you the diff, or difference, between the old file and the file with the new changes. There are two common styles of showing the diff: unified and split. Whenever possible, I use split, which will show the old file and the new file side by side. I find unified, where it shows one file with the old line of code directly above the new line of code, difficult to follow.

This is one of the times that git will need to open a window to allow you to edit something. If nothing is configured, git will default to a vi window. This is the reason I have the vim command cheat sheet bookmarked. You can also associate a text editor with git so you can do this stuff outside of the terminal window. VS Code's integrated source control management allows you to associate VS Code with git in a GUI. If you've triggered conflicts in GitHub, it will open a new view in the browser.

To resolve conflicts, you choose the changes you want to keep. Typically they're represented like

<<<<<<<

old file

=======

new changes

>>>>>>>

Sometimes it's as easy as deleting the changes you don't want and the markers (the caret and equals signs) and saving the file. Check out GitHub's documentation and VS Code's documentation for step by step examples.

After you resolve all the conflicts, you add the --continue flag to the command that triggered the conflicts like

git merge --continue

If you get overwhelmed, you can always escape by running

git merge --abort

If it gets really bad, you can always cherry-pick your commits onto a new branch.

Fetching

What if you're just looking to get the latest commits from the remote repo? Running git fetch will fetch all the remote changes you don't have in your local repository.

This means if you really really mess up, you can run

git branch -D <branch-name>

git fetch <remote> <branch-name>

The -d and -D flags stand for delete. Capitalized -D will delete a branch even if the changes aren't in the remote. Lower case -d will not. Neither will delete the remote branch, only the local.

If you run git fetch, it'll fetch all of the changes from the remote repository.

If you configure fetch to prune, like so:

git config --global fetch.prune true

It will remove things like old branches you've deleted in the remote too.

Pulling

You could say pulling is the opposite of pushing. Like pushing, git pull is the same as git pull [remote] [current branch]. However, pushing, like fetching, only looks to update your commit information.

Running git pull is the same as running git fetch and git merge or git rebase. This is why you'll often see people merging changes into a branch by checking out branch-A and running git pull origin branch-B.

By default, pull is set to use git merge. This means when you pull, you'll often generate a merge commit, combining remote and local changes. You can update this by running

git config --global pull.rebase true

This will pull commits down, won't trigger a merge commit, and usually involves fewer conflicts.

A word of warning: I often checkout a branch, see a log saying the branch is up to date, pull, and then see changes were fetched.

More Resources

Learn Git Branching is an interactive tutorial with visualizations that is very helpful for all levels.

If this is your first introduction to git, I highly recommend putting what you just read to use with Git-it. It'll walk you through entering the commands yourself. Truly the best way to learn git is to try it, mess it up, and fix it over and over again.

If you want all your git options in one place, that's the git reference documentation.

I personally like the Atlassian tutorials because they spell out concepts in plain English and have a lot of diagrams.

If you've truly hit #gitPanic, Oh Shit, Git!?! has your back (and Dangit, Git!?! has it without swears). The amazing Julia Evans also has a zine by the same name.

Conclusion

Now that we've covered the basics of how git works, I'll talk about the basics of working with other developers in a repo next.